My bushcraft, hiking and other outdoor activities have always been motivated by a love of the natural world and a desire to spend more time learning to understand and appreciate it. To me the other side of this equation is a responsibility to try to minimise the damage I cause to the living world I love, and even to go beyond and work to remedy some of the damage we as a species have collectively caused to it. The starting point is leaving no trace while out exploring, not leaving litter or fire scars for example, but this quickly spread to thinking about the traces I left when I got home. If I’m using minimally harmful soap and washing up liquid when I’m camping, shouldn’t I use it at home too? It all ends up in the same place eventually, at home it just takes a little longer to get there via the sewage system.

I try to minimise the impact of my adventures by getting public transport to my starting points if I can. I also try reduce resource consumption by buying as little equipment as possible, always trying to source second hand and repairing or having repaired whatever I can to extend its life. I still have the tent I bought when I was 18, the only intelligent purchase of my teenage years, which has been reproofed and mended many times and had new pegs and poles from TentSpares, and when my rucksack finally disintegrated beyond the ability of my sewing skills to repair and my sleeping bag zip broke I sent them off to Lancashire Sports Repairs who did an excellent job of rejuvenating them. At times this philosophy can feel a little like swimming against the tide as there does seem to be a substantial section of the bushcraft community apparently mostly focussed on buying the latest, highest specification kit, but it really is unnecessary to spend a fortune on new stuff to get into the hobby. And as one of the main ways we as humans are harming the planet is by mindless overconsumption, it always seemed a little perverse to facilitate appreciating the natural world by buying a lot of the shiny gadgets whose production is destroying it.

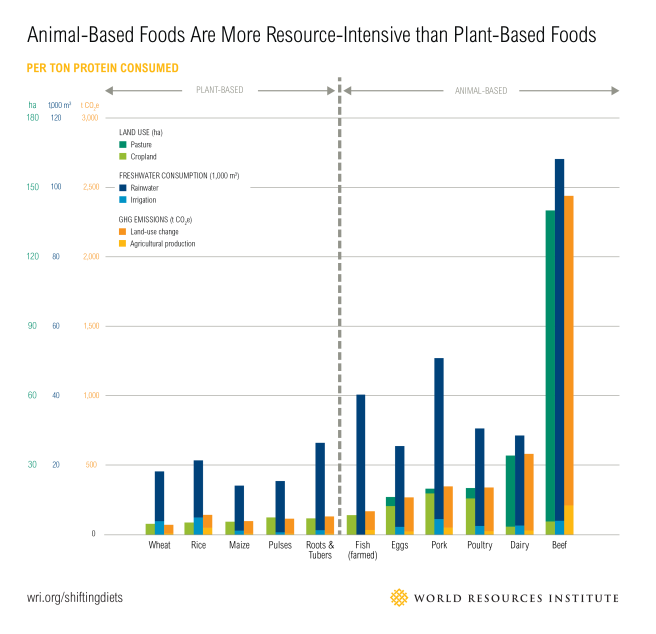

Increasingly however we’re becoming aware that one of the easiest ways to reduce our impact on the planet is to reduce our consumption of animal products. Whether in terms of water use, land area use or fertilisers and pesticides used to grow crops it’s simply more efficient to eat plants directly than to feed them to animals with a proportion wasted along the way and then eat part of the animals. And that doesn’t include the environmental impact of animal waste, or the warming-causing methane released into the atmosphere from ruminant digestive systems. While beef is one of the worst offenders for environmental impacts all industrially farmed animal products suffer from the same problem to some extent.

It is true that the situation isn’t quite as cut-and-dried as all meat bad, all plants good: skipped meat, roadkill and venison or squirrel from animals that would have been shot anyway as part of a sustainable woodland management campaign will have a negligible impact for example, whereas green beans airfreighted in from Kenya and grown in glasshouses discharging fertiliser into Lake Naivasha will be doing more harm than good. But generally speaking, reducing your consumption of animal products is a quick win environmentally. There do seem to be some people who interpret any suggestion to reduce their meat consumption as an existential threat – I’ve left a few online bushcraft communities who seem to believe their ability to read the subtle signs and locate and subdue a packet of bacon in the Morrisons freezer makes them a mighty tracker. But even if you can’t give up meat entirely eating less and eating less damaging types will still reduce your impact.

Certainly animal products have the advantage of being very calorie and nutrient dense, which is useful when carrying all your food on your back – cheese and peperoni are backpacker staples for a reason. But with a little thought you can select vegan foods that serve just as well, and even have some advantages compared to animal products. They’re a lot less likely to go bad in hot weather, and as the cost of living crisis bites, plant-based foods can often be cheaper than animal derived ones. I’ve recently started shopping for my parents who buy meat and fish and been quite shocked at the amount a shopping basket costs for them vs for me.

Below I’ve gone into detail on the typical vegan food I would take for the three day solo hike. I’ve often gone into slightly obsessive detail about not just the most ethical food but often the most ethical brand and the most ethical suppliers, and I acknowledge being able to do this is a product of privilege in terms of money, time and mental energy. Times are hard and exhausting right now, and we’re all doing our best. I’m putting this post out there for information not so anyone feels shamed or judged for not doing the same. In an ideal world the least damaging foods would be the default, not the more expensive or inconvenient option, and as well as trying to minimise my personal impact I’m campaigning to make that world a reality. I hope we see it someday.

Breakfast

I make my own muesli with oats and dried fruit, nuts and seeds bought in bulk from either Real Food Source or my local Zero Waste shop, which I’ve found to be much cheaper than buying it ready made from the supermarket. The great thing about muesli is you can eat it cold or heat it up on chilly mornings to make fruity porridge.

I transport the muesli and some other dried produce in Onya Bulk Food Bags. Ziplock bags would work just as well, and indeed I do use ziplock bags for packing toilet paper and other hygiene waste out, but the great advantage of these bags is that they’re almost infinitely reusable. Normally I’m very against buying specialist items in the interests of sustainability as you’re just consuming more in the interests of consuming less, and it creates the perception that reducing your impact on the planet is something only people with money to spend can do, but I use these in my day to day life as well as we have two excellent Zero Waste shops in Exeter and it’s really useful to have fold down bags in my bag at all times in case I pass them unexpectedly, rather having to plan around transporting bulky containers. They also have the bag weights already conveniently printed on the bag.

I’m still searching for the holy-grail of a perfect dehydrated plant milk, but the best I’ve found so far for coffee and muesli is Coconut Company Coconut Milk Powder. It dissolves best in hot water, and even then you’ll need to spend a meditative minute every morning squashing lumps against the side of your mug, but it’s satisfyingly creamy in coffee has a mild coconutty flavour. This one gets transported in a small Tupperware box, rather than a reusable bag, as it’s a bit greasy and harder to clean out of the bag. Unfortunately the only place I’ve found it is a company owned by someone who’d rather launch himself into space than give his workers toilet breaks, so if anyone know of a better source (or indeed a better milk) please let me know.

You need some luxuries even when travelling light, and the one thing I can’t do without is good coffee, which I pack in another Onya produce bag. I get mine from Pact Coffee, a subscription service for sustainably grown single estate coffee subscription from fairly paid farmers, and full disclosure if you follow that link and take out a subscription we both receive a £5 off voucher.

Something I don’t bother bringing is tea. While the idea that you can supply yourself with enough calories or protein by foraging while hiking has been pretty thoroughly debunked, tea is a different matter and between nettle top, sorrel, elderflowers, ground ivy, linden tree flowers, wild mint and thyme, gorse flowers and western red cedar shoots I can usually find something nice to infuse in hot water almost any time of year and in most British landscapes.

Lunch and snacks

Oatcakes are not only more calorie-dense than regular bread, packing more energy into a smaller area, I also find they’re less squashable or crumbleable than bread too. While they do contain palm oil, Nairns only uses palm oil that is certified as sustainable by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil which means it is only grown on land that has not been cleared of primary forests, and its supply chains are entirely traceable. Nairns is a pretty environmentally aware company as they go, using locally grown Scottish oats, powered entirely renewable electricity and sending no waste to landfill so personally I’m very happy eating them.

Peanut butter is an excellent calorie dense spread for the oatcakes. Obviously transfer it from the glass jar into a tuppeware box first, I like the Addis Clip and Close ones because they stop the oil seeping out. I’ve also tried Sistema boxes, which didn’t work so well. There’s more on the challenges of transporting oily things at the end of the post.

I also like taking carrots as a snack – it’s nice to have something fresh on the trail and unlike fruit they don’t squash or bruise. I like to dip them in the peanut butter – everyone I’ve ever mentioned this to has reacted with horror as though I’ve confessed to some unspeakable perversion, but I thought I’d share the tip anyway just in case someone reading this has taste.

I’m sure everyone has their own favourite snacks, but chocolate, fruit and nuts or granola bars work for me. Traidcraft has a good selection of fairtrade nuts and dried fruit.

Dinner

I’m not a great fan of pre-prepared dehydrated meals – they come with a lot of packaging, and seem very expensive for what they are. While obviously if you’re doing a long through-hike and need to resupply en route, if I have time to prepare I prefer to make my own using dehydrated soy chunks for protein, noodles for carbohydrate and packet soup for flavour.

I also add in dried vegetable slices that I make myself in the dehydrator. Again I wouldn’t encourage anyone to go out and buy a whole machine just for one hiking trip, but in my case it’s been very useful for foraged food and home grown vegetables. Carrots, mushrooms, courgettes, cauliflower and golden beetroot all work well (regular beetroot is too messy). You want to cut things into very thin slices and get them dry to the touch so they don’t have enough moisture to go mouldy, but not dry enough to be brittle so they crumble to powder in your bag.

Combining all of the above and adding it to boiling water makes for an extremely tasty dinner if I say so myself, and at the right time of year you can liven things up and provide a bit of variety by adding wild garlic, sorrel or pepper dulse.

Transporting oil

As we all know, the greatest unsolved puzzle currently facing humanity is not ending world hunger and disease and learning to live in harmony with the environment, but how to transport oil when camping without it leaking all over your bag. No matter how securely you seal the container, as soon as you pour some out it gets on the lip and, unlike water-based liquids, never evaporates so just sits there making your container leak and lubricating screw caps to fall off. The best solution I’ve ever found is a little clip and close glass bottle, but I keep that in a ziplock bag just to be sure. It works better than anything else I’ve tried though, and I’ve tested it by taking it for a 5K run just in case anyone was still labouring under the mistaken belief I was in any way sane.

A glass bottle isn’t the most lightweight solution, but I don’t tend to fry things when I’m hiking anyway – you need an extra pan, things that can be fried are generally more bulky to transport and it’s much easier to clean oily things in a campsite with sinks and hot water in any case.

One thought on “Lightweight plant-based eating outdoors”